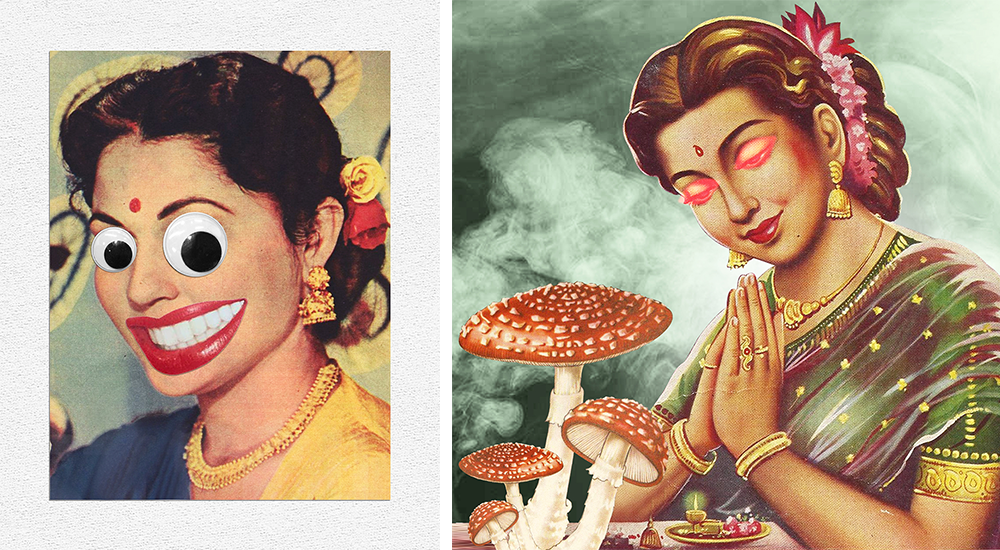

Psycollagist’s art couples the nostalgia of a bygone India with a sharp bite of humour

Meet the man behind Psycollagist and his strange yet humorous montages that splice together vintage imagery to create riotous, multi-layered worlds.

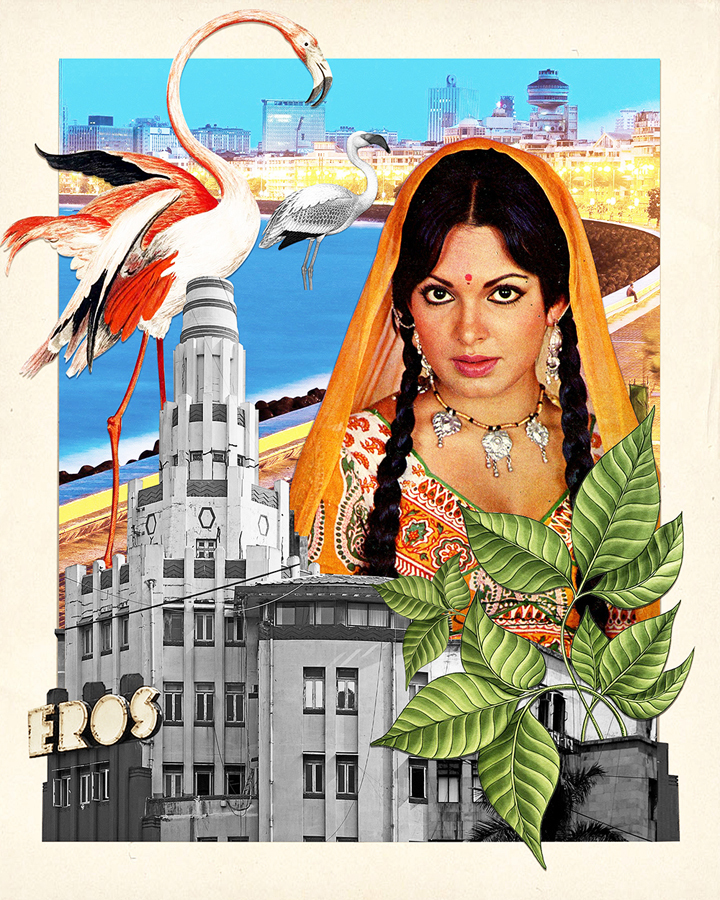

Earlier this year, Vishwajeet Talwadekar a.k.a Psycollagist took a leap of faith and left behind his job as an Art Director to launch his practice as a collage artist. His penchant for making collages began as a hobby, and stayed with him through the grueling years working in the advertising industry. Using vintage imagery from India, his artworks are born serendipitously, with the story and visual finding each other somewhere along the way.

His tongue-in-cheek collages reference cultural icons, mythology and the history of cannabis in India, without ever losing the humorous undertone that defines his work. Vishwajeet chalks out his evolving relationship with the medium and the importance of stripping off all sense of control as a collage artist.

You spent five years working in the advertising industry and just this year, launched your independent practice as a collage artist. What made you change track?

I passed out of art school and went on a sprint for a few years, working with a handful of advertising agencies. I began interning as a graphic designer not because this was something I really wanted to do, but just as a means of supporting myself as a young graduate. Within a year of the job, I was promoted to the position of a Visualizer and thereon rose a few rungs up the ladder and became an Art Director. And yet, I was constantly nagged by the realisation that I wasn’t happy with the work I was making. I felt like I had a lot more to give as a creative individual. The shift to becoming an independent artist was spurred by an almost selfish drive to make work for myself that I was happy with. Back then, quitting advertising seemed like a drastic decision. But it eventually became a foundation for a new beginning.

I have been cutting up scraps of images and putting them together for as long as I can remember. As a child, it was just a fun exercise. But in 2016, when I approached collage-making as something I wanted to pursue as a vocation, I realised that the medium was boundless. So I used this time to create more work and slowly started sharing it on Instagram. I got a brilliant response from my followers and within two months of setting up my own page, I sold my first print. Since then, things gradually started to take off and I realised that I couldn’t possibly keep living both these lives, one of an artist and the other of a full-time Art Director. So I chose the former and never looked back.

What has been the most challenging part about going solo?

I create my artworks, get them printed, framed and sometimes even hand-deliver them to my customers. I enjoy how personal and intimate the entire process is. But at the same time, it is a one man show. The biggest challenge is to always be on your toes and never stop creating. But the rewards are growing by leaps and bounds. Recently, a few Indians living in London and Scotland reached out to me through Instagram, and I shipped them some prints. It feels great to be discovered by a diverse range of people living in different corners of the world, and the conversations that follow about how they perceive my work is all the inspiration I need to keep making more art.

If you were to trace back to your childhood, can you now recognise the factors that contributed to your journey as an artist?

I was brought up in Mumbai and from quite a young age, I was inclined to creating things. We were growing up around the time when print media was exploring exciting new avenues, so we were exposed to a lot of paper material like newspaper inserts, pull-out magazine ads and comic books. I remember my childish experiments like inking the teeth of the lady in the ‘Sumeet Mixer Grinder’ ads, drawing hair with color crayons on pictures of bald people and tearing apart magazines to use in collages. There was a certain sense of fun in keeping and collecting these small senseless creations.

I wasn’t the best at school and detested studying. As a result of my infamous habit of tearing things up, chapters from my textbooks started disappearing. Every notebook of mine was incomplete but filled with mad scribbling. Back then, if you happened to be a kid who was only good at drawing and bad at academics, you were labeled as a ‘problem child’. The fact that I was terrible at all subjects made me want to find that one thing I could be good at. That’s how I arrived at art.

Two years ago, when you went back to making these psychedelic montages, what got you hooked to the medium?

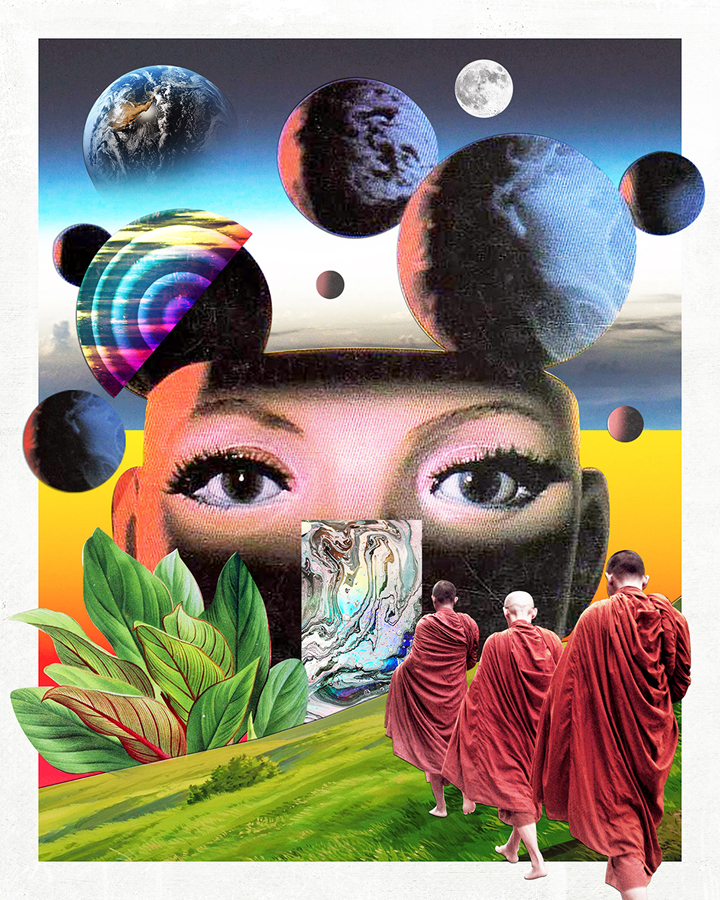

For me, the ‘art’ is in the entire experience of creating the work. Sometimes the exercise of putting unexpected images together leads to an artwork that my mind couldn’t possibly have constructed otherwise. Getting lost in the experience and letting my hand guide my brain is as therapeutic as meditation, and that is probably what pulled me back in. The creative process is led by intuition, and as an artist, you have to give up your sense of control. I call it a state of the ‘possessed hand’, where it brings the collage together without the mind guiding it. When the disparate pieces begin to tell a story, I start shaping the narrative by keeping and discarding pieces of images and observing how each element adds to the artwork.

Where do you pick up the the archival Indian imagery that features in almost all your artworks? Are there any copyright legalities that you keep in mind?

I am constantly digging through vintage magazines, archives and public domain sites to collect pieces for my collages. It is surprising how you find the best imagery on websites that look like they have nothing to offer.

Talking about the legalities, there are a lot of grey areas in collage copyright laws. So it’s always better to used really old images or pick them up from a public domain archive source.

The Bhagavad Gita has a strong influence on your work. What about its ideology speaks to you?

Our entire Indian culture has always been rich in spirituality and revolves around the concept of self exploration. All our ancient literature, including the Tripitakas, Bhagavad Gita, Quran, Guru Granth Sahib talk about the importance of creating a harmony between the body, mind and soul. The Bhagavad Gita inculcates the importance of living your own destiny imperfectly over imitating somebody else’s life with perfection. At its very core, the scripts teach us to be true to ourselves. As an artist, that was one of the most important learnings.

The cannabis culture in India is a recurring theme in your work, but instead of making it a strong political statement, you add your signature dash of humour, almost transforming them into memes.

Yes, these artworks are a celebration of my relationship with cannabis and not an attempt to take a political stand on its legalisation. I find it strange that cannabis is still considered a taboo in India when it has such a long-standing history in our culture, veiled in legends and mythological texts. The earliest mention of cannabis has been found in the Vedas, which mention it as one of the five sacred plants with a divine consciousness living in its leaves. The Vedas call cannabis a source of happiness that was compassionately gifted to humans to help us attain delight and lose fear. It is a herb, and if used correctly, it can indeed contribute to a greater collective evolution.

Surrealism is an integral part of your art. Who are some of the artists whose work left an impression on you?

I’ve found inspiration not just in the oeuvres of Surrealists like Salvador Dali but in the works of M.F Hussain, Henri Matisse, Van Gogh, S. H. Raza, Vasudeo S. Gaitonde, Joan Miró, Giorgio de Chirico, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock and Alex Grey.

Give me a glimpse into the pieces you’re working on currently.

I am working on a series of collages that revisit nostalgic objects that are intrinsically tied to our lives in India. Growing up in the 80s, one of my strongest memories is of the Fiat cars lining the streets of Bombay. My family never owned one, but there was an uncle in the neighbourhood who would religiously wash his Fiat every Sunday morning and take the kids of the colony out for a drive. That car was a cultural icon of life in Bombay back then. I want to create something with an image of the steel canisters that the doodhwallas carry, strapped to their cycles when they come riding down our streets every morning.

This article was originally published on Design Fabric.