Minimalism gets a voluminous redux in Chola’s latest collection

Two years since she launched Chola, Sohaya Misra has defined a design vocabulary that is at once striking and unmissable. Through the Summer 2018 collection, she lets us in on the subtle hybridity of her ensembles.

Fashion in India is bone-tired of minimalism. With a plethora of lookalike labels creating garments that are barely different from another, the idea of minimalism is hardly ever challenged. Yet Sohaya Misra of Chola manages to break the mould with an understated ease. Crafted with tactile fabrics like linen, organic and handloom cotton, she uses the simplest of elements to create dramatic ensembles. The silhouettes are voluminous, with cascading folds that envelope the body and lets it move effortlessly.

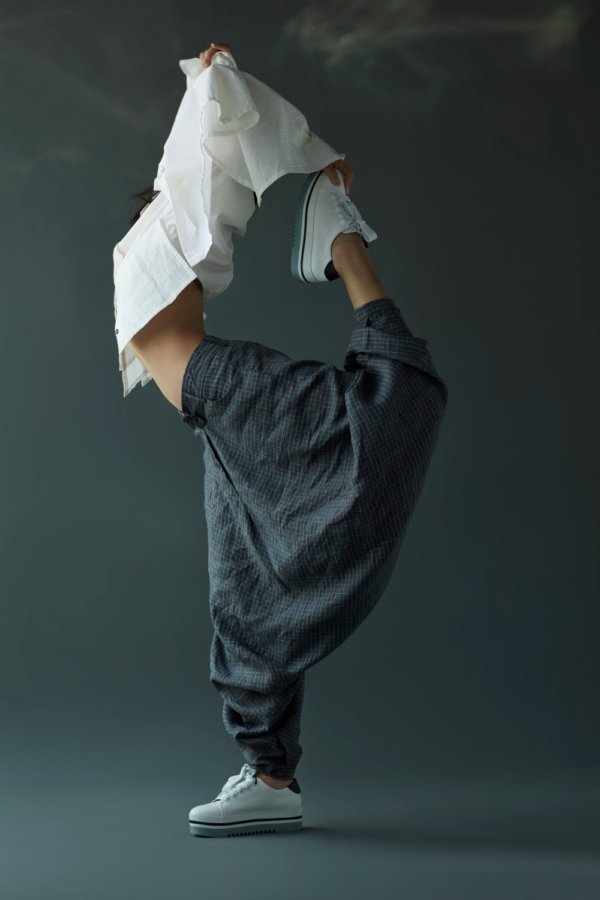

In Chola’s Summer 2018 collection, sleeves become frilled wings and garments shape-shift as trousers moonlight as skirts. The lines keep blurring and shirts transform into overlays, till it’s neither a shirt nor an overlay but a bit of both. It is this sense of mystery that fuels Sohaya’s creativity.

As we connect over a phone call, the designer tells us how she stumbled upon her passion and everything that followed.

Your clothes are sharp, minimal and never feature any surface embellishment and that stands true for your Summer 2018 collection as well. How did you start conceptualising the collection?

Each season begins with a hunt for fabrics with maximum texture and fluidity, and that dictates the direction of my collection. I don’t start with a consolidated plan in mind. The fabrics start speaking to me, I listen and capture that dialogue. My creative process completely relies on serendipity and a lot of trial-and-error. However, sometimes it begins with the details.

For the Summer 2018 collection, I remembered some visual references I’d collected of frills done uniquely. So I started with a few snips of the scissor, trying to imagine how I would interpret this element in my own way and give it a dramatic twist. Surface embellishments have never been my forte, and I don’t think they find a place in my style. I have always been a passionate believer of the ‘less is more’ ideology. Adding embellishments to that would take away from what I’m building. So I’d rather keep it clean and minimal yet not underwhelming.

In the campaign for Summer 2018, the model walks, crouches, squats and at an instant, and is almost caught dancing. Were these images a hint at the functionality of your anti-fit silhouettes as enablers of movement?

Definitely, my clothes are all about letting the body breathe and move. Whenever I cut a certain pattern, I make someone wear it just to see how it moves when a person is sitting, walking or running. For me, the challenge with Chola was to crack the code where my silhouettes are functional and yet dramatic because most of the times, you only get one or the other. I also try to put in certain details that amp the playfulness of the pieces and let the wearer make the garments their own, without hampering the way the body shifts, turns or twists.

For example, in Summer 2018, one of my longer shirts have loop-in buttons. When you button it up, the fabric folds and creates different shapes. Also, the drawstrings at the seams allow my customers to cinch up a shirt where the length shortens, or leave it open and create a billowy shape. My idea is not to set a certain vision for a garment and hand it over to someone. I want to let them make something out of it too so that it sparks the creative streak in them as well.

Do you follow a certain process to arrive at the mood and tonality of the colours you're using in a particular collection?

The monochrome palette has always appealed to me; for a long time, I could only think in black, white and grey. Breaking into other hues was a challenge for me. But for Summer 2018, I narrowed in on a jewel palette, with a lot of burgundy, rich purple, olive green and slate grey. All of the hues are desaturated, which brings the entire collection together beautifully.

You majored in psychology and then shifted to fashion styling. When did the idea of pursuing fashion design finally kick in?

Right after I completed my degree in psychology, Manisha Koirala, who happens to be a close friend of my mother’s, reached out to me to do the styling for her 1999 movie Mann. After that, I worked on quite a few styling projects until a friend of mine who runs The Vintage Garden here in Mumbai asked me to make a capsule collection for a pop-up. I went to a fabric store in Delhi and picked up a trove of different textiles and created around 30 pieces that flew off the rack the very first day. I remember staying up all night with my tailors to create 10 more garments to put back on the rack for the next day. That’s when it hit me that I might be onto something. Each customer told me how the pieces were comfortable, wearable and edgy and I wanted to build on that and create my own signature. That’s where the idea of Chola was born.

What led you to the distinctive Chola aesthetic?

Before I began Chola, I was looking at the works of Japanese designers like Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto. It’s inspiring to see how Yohji’s clothes are minimal and yet so complex. The garments are draped in such a way that you can’t always tell what piece goes where, until is in worn. There is a sense of mystery to it. I wanted to inculcate that into my craft as well. As much as I love to revisit the classics, and challenge what a white shirt could or should look like, I also enjoy dropping the crotch in a trouser and turning in into a skirt where the garment becomes neither and yet both. Some of my jackets have long strips of fabric dangling from the shoulders, but you can’t always tell if it is a part of the shirt or the overlay. I like to challenge how the mind thinks. The Chola aesthetic was conceived somewhere between this interplay of the obvious and the peculiar.

You work extensively with separates that can be swapped with each other to create fresh new ensembles. Why is transitionality so important to you?

Other than being transitional, my clothes are age, body shape and gender agnostic. Inclusivity is important to me. Sometimes granddaughters and grandmothers come to my studio together, and I make sure that each of them find something they’re happy with. Recently, men have been picking up my jackets and trousers as well. I never wanted my clothes to be limited to a certain sector of people.

The transitionality of the separates is my way of working against the fast-fashion industry. You don’t need to clutter your wardrobe with a hundred garments that can only be worn one way. It’s such a waste of natural resources, like the water that you use to wash your clothes as well. Sometimes, I even ask my clients to come in with their old Chola pieces to see if I can turn a shirt into a jacket, or a dress into a skirt instead of simply trashing it. Fashion should be fun, expressive and most importantly, responsible.

This article was originally published on Design Fabric.