Decades Later, India’s First Graphic Novel Has Found a Cult Following

Illustrators have long been visiting Orijit Sen’s store to photocopy his last copy of River of Stories. Now it’s due for a reprint

Tucked into a quiet corner of Orijit Sen’s studio lies a dog-eared copy of River of Stories, one of the only surviving hardcopies of the first graphic novel to be published in India. Tracing the Narmada Bachao Andolan, a series of protests in the early ’90s, River of Stories builds its narrative around the controversial construction of dams across the river Narmada, which rises from a plateau in the state of Madhya Pradesh. The dams ultimately displaced the lives of thousands of indigenous people in the area.

Sen, who studied graphic design at the National Institute of Design (NID) in Ahmedabad, has carried this copy of his now cult-famous novel over decades and across cities, moving from Delhi—where he created it—to the sunkissed city of Goa, where he lives today. I, however, have never seen River of Stories in its physical form. When I first discovered the novel on a sleepless night back in college, it was as a PDF I downloaded from the internet, and that too has traveled with me across cities, jobs, laptops, and flash drives. Published in 1994, the novel has been out of print since the late ’90s, though the digital version and rare copies still circulate within the creative community in India. After rumors started circulating earlier this year that a new edition was in the wings, Sen finally confirmed that he was ready to revisit his debut work.

Years before Sen first arrived at the idea for River of Stories, his introduction to graphic novels came by way of Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman, whose work he discovered in the libraries of NID. “While in school, I’d read a lot of Tintin and Phantom, the comics that were usually available at the time, but it was in the ’80s in college that I came across underground comic artists like Crumb,” he tells me over the phone. By the time Sen read Spiegelman’s Maus, which had just won a Pulitzer prize, he had made up his mind to make a longform comic, he just didn’t yet have an idea for what it would be about.

By 1990, Sen had set up the alternative design and crafts store People Tree with his wife Gurpreet Sidhu. While the couple, who met at NID, set up shop and started screen-printing their now iconic T-shirts, Sen also became involved in the ongoing Narmada Bachao Andolan as an activist. “I used to make posters for the andolan (movement) and also take part in demonstrations,” says Sen. The protests were spearheaded by indigenous peoples (adivasis), activists, farmers, and environmentalists to resist the construction of dams across river Narmada. They questioned the government’s plan to introduce industrial structures that would wipe out the agricultural know-how that indigenous people had handed down through generations. “I started traveling to the Narmada valley to take part in the protests, and it was then that I suddenly realized: my graphic novel needed an idea, and I’d just found it.”

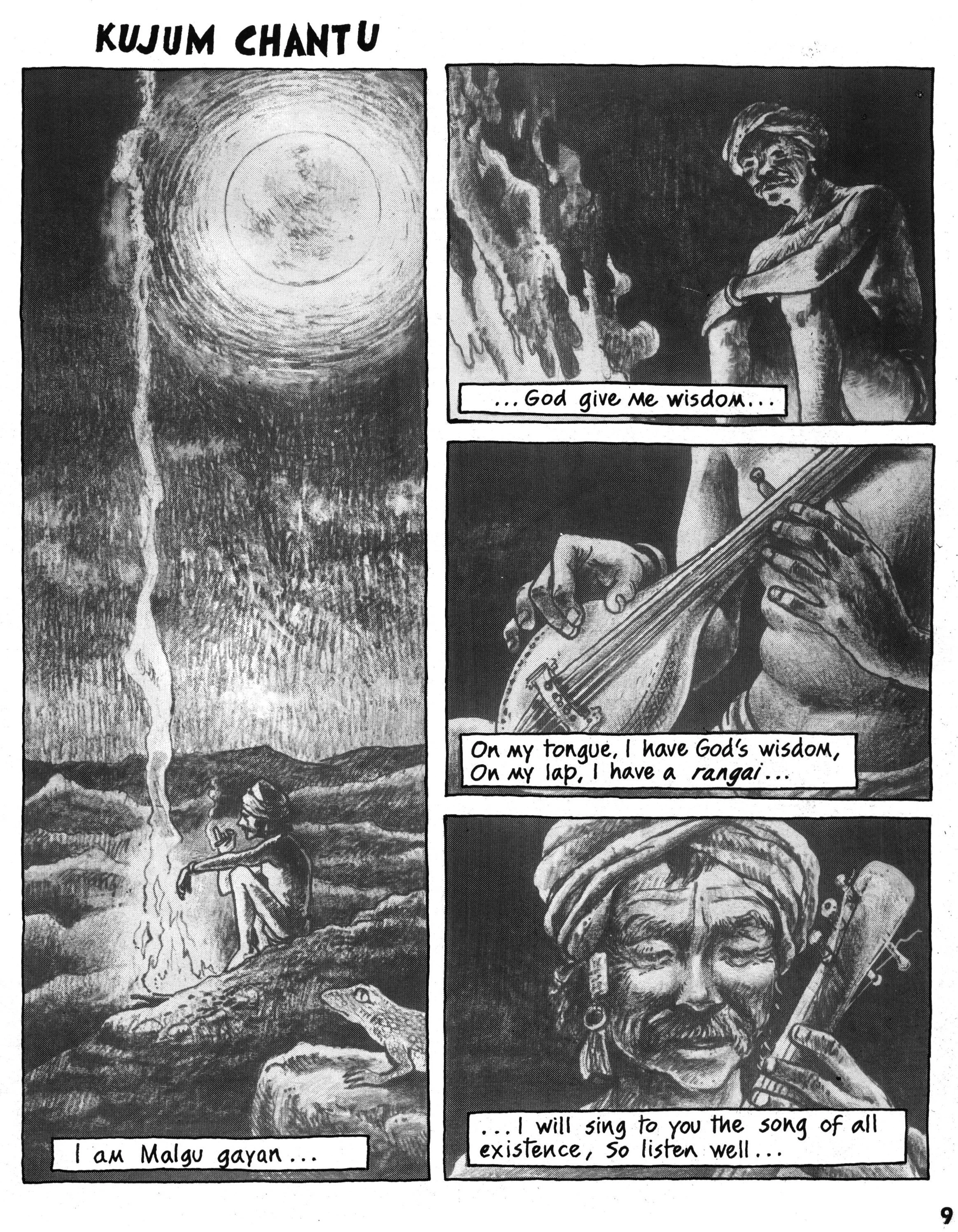

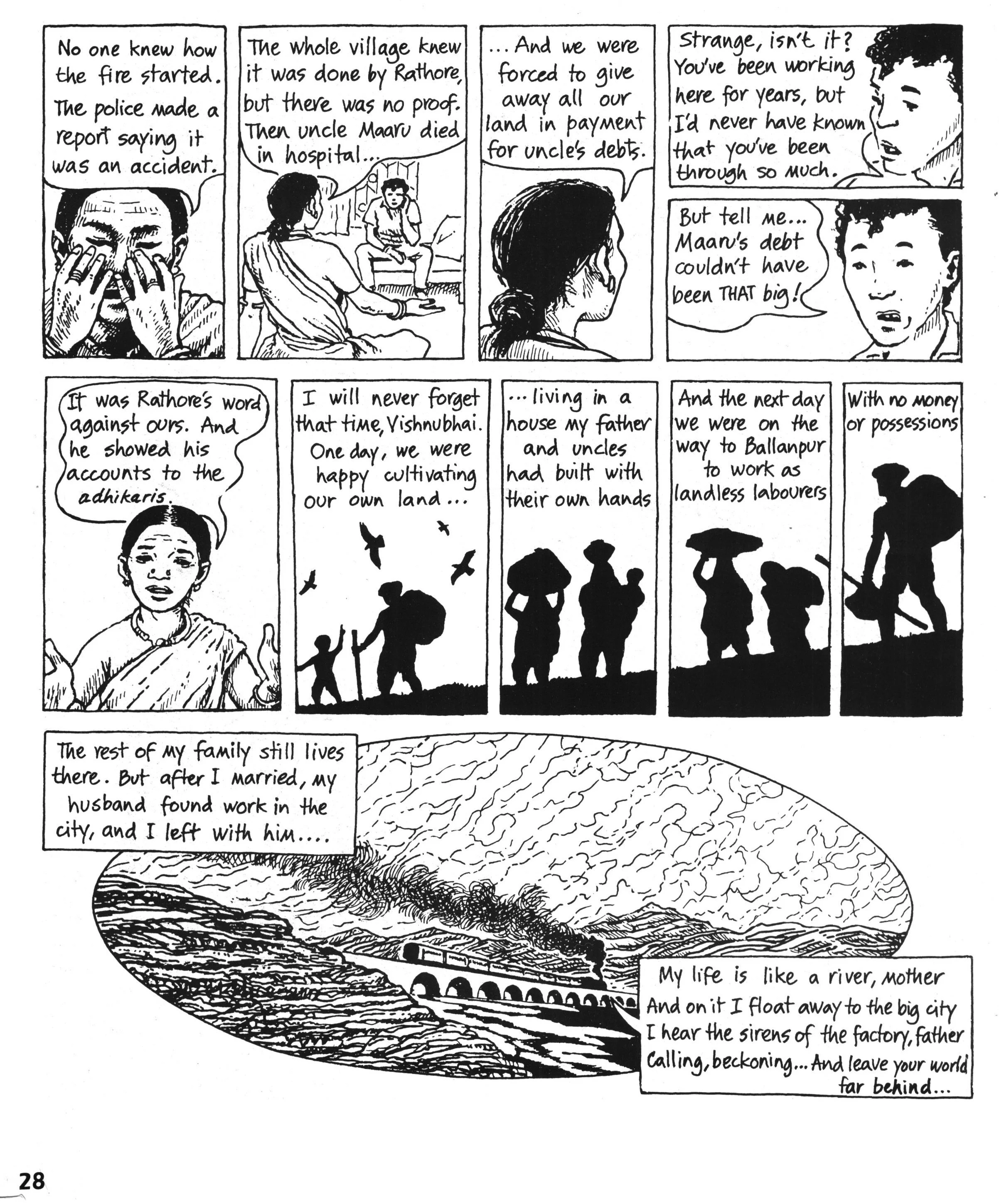

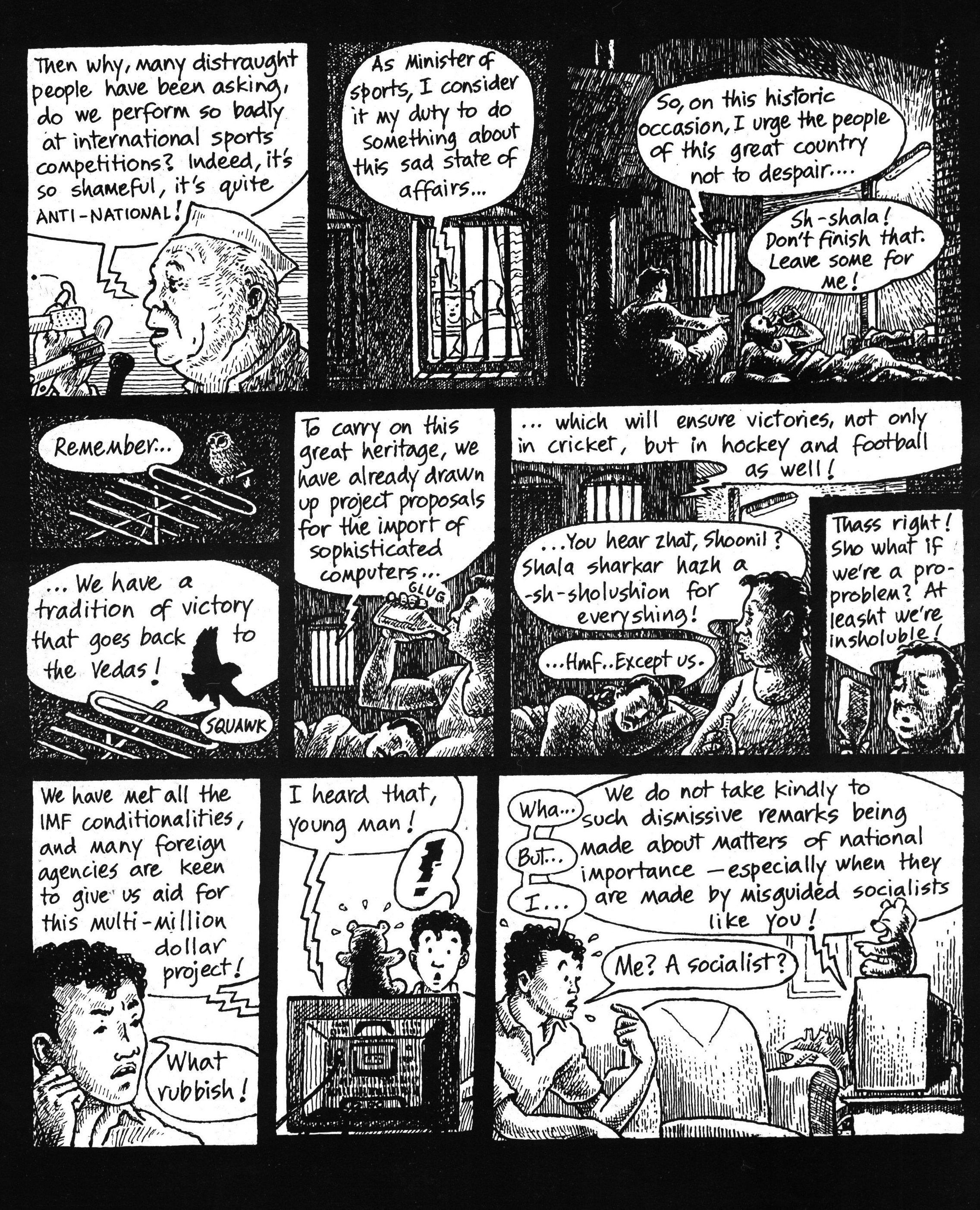

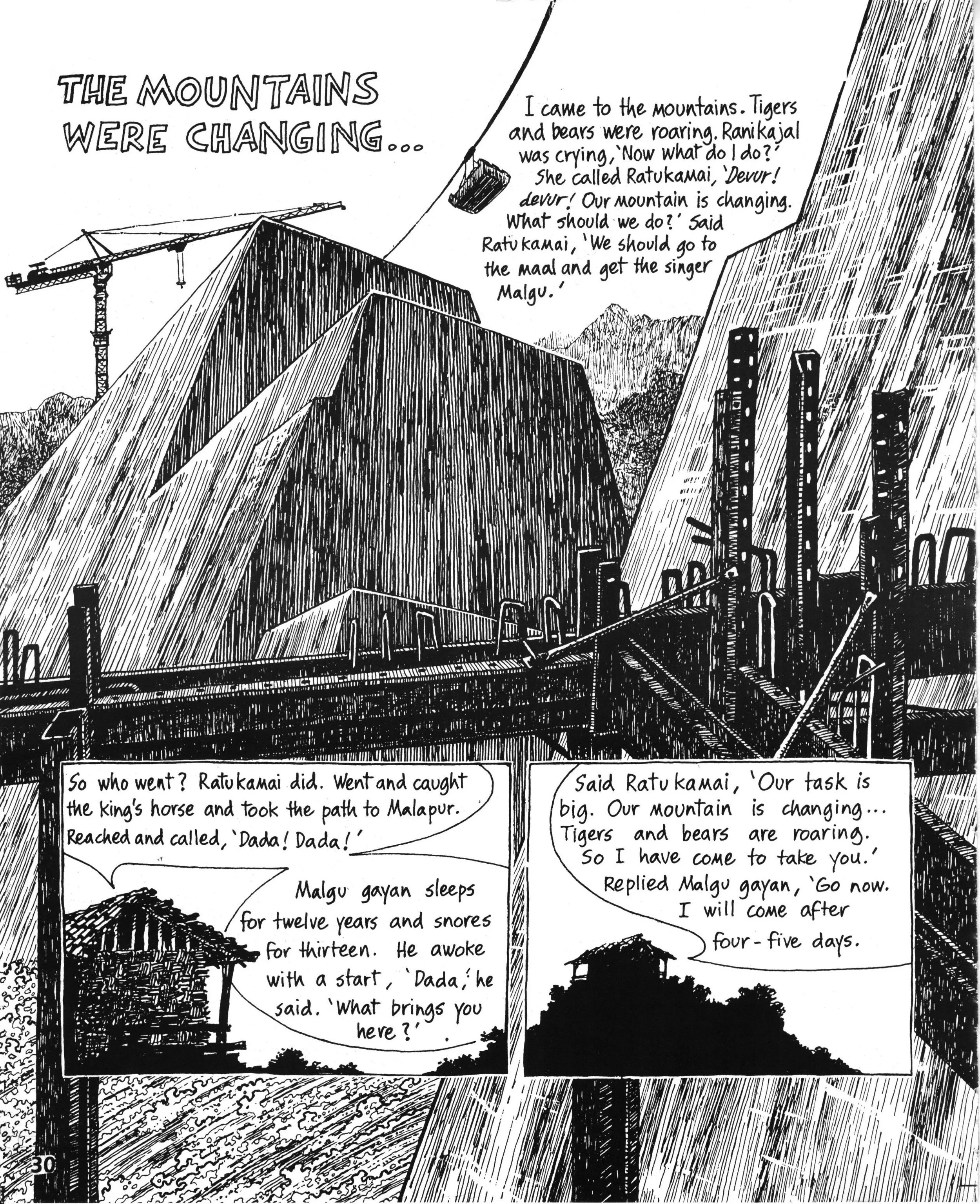

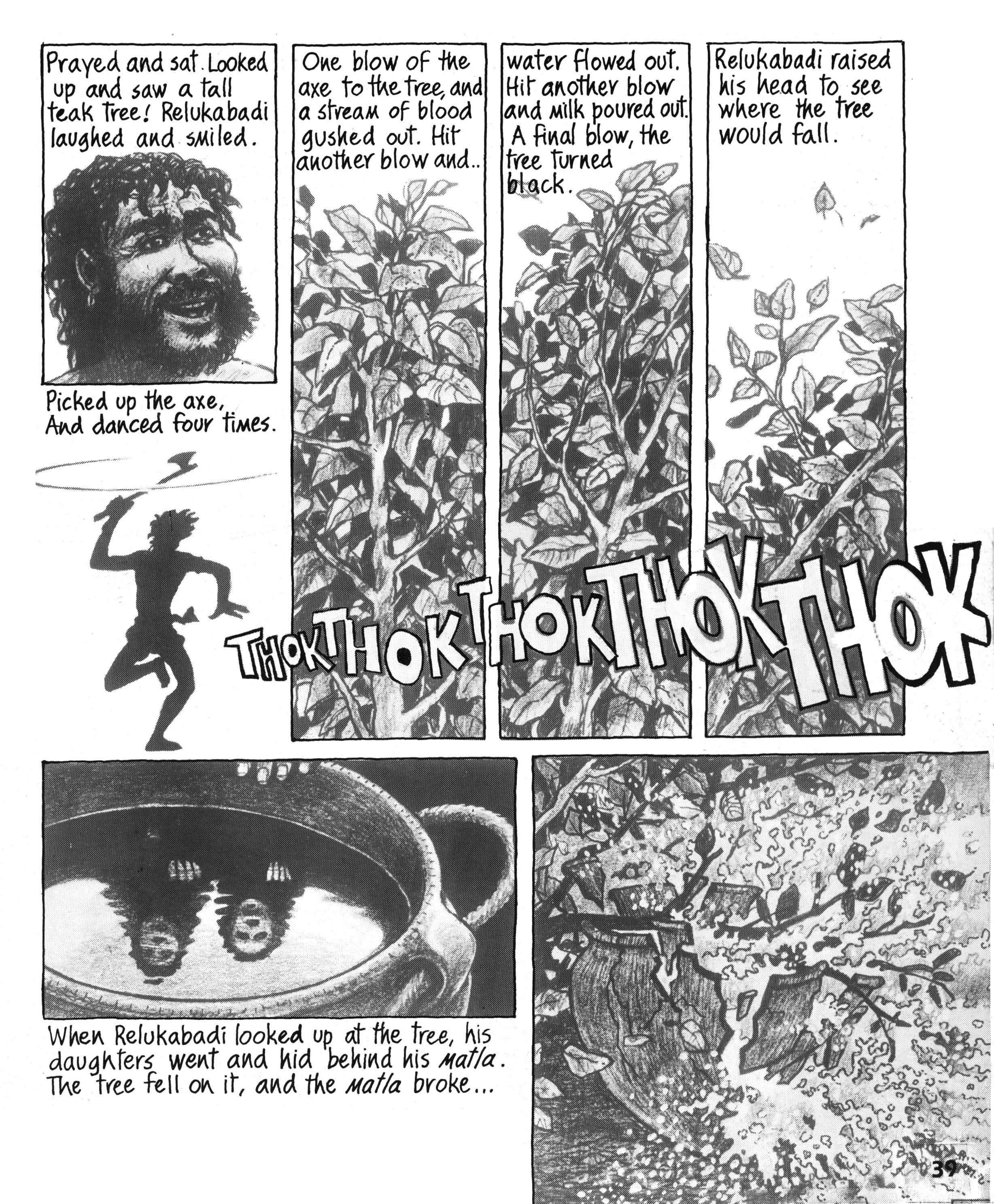

Back in Delhi, Sen turned a small room at the back of the People Tree store into his studio and began working on River of Stories. Over 62 pages, the novel stitches together two disparate narratives; one follows Vishnu, a young journalist from Delhi who travels to the valley to document the protests, and the other taps into mythologies of the adivasis to recount the tale of a singer called Malgu Gayan, who strums his rangai and sings of the creation of the river. Vishnu’s story unfolds in a fluid, almost linear illustrative style, while the more mythical sequences take on a heavily-shaded, painterly aesthetic. As the story progresses and the narratives intersect and flow into each other, the two styles also begin to meld together.

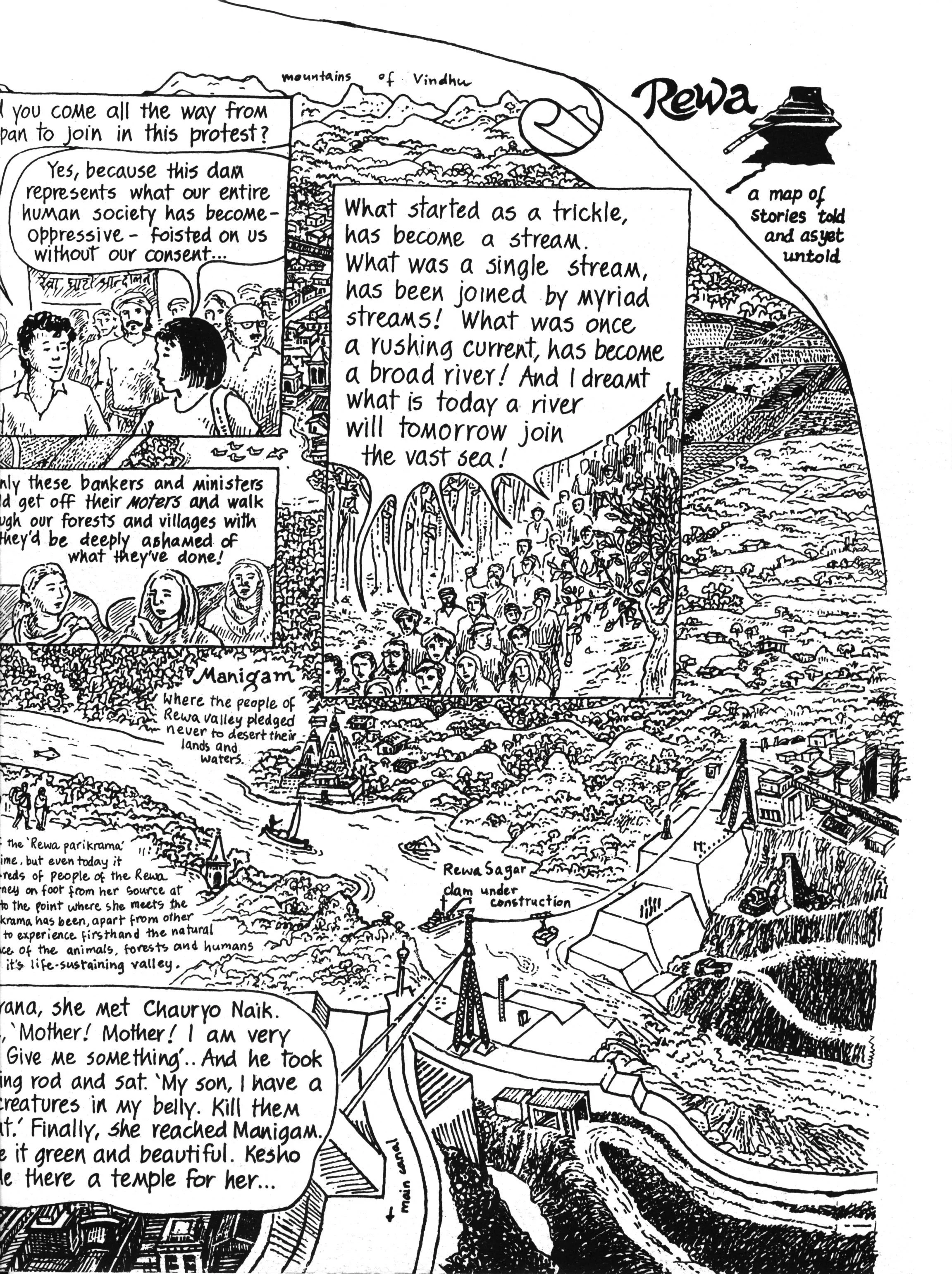

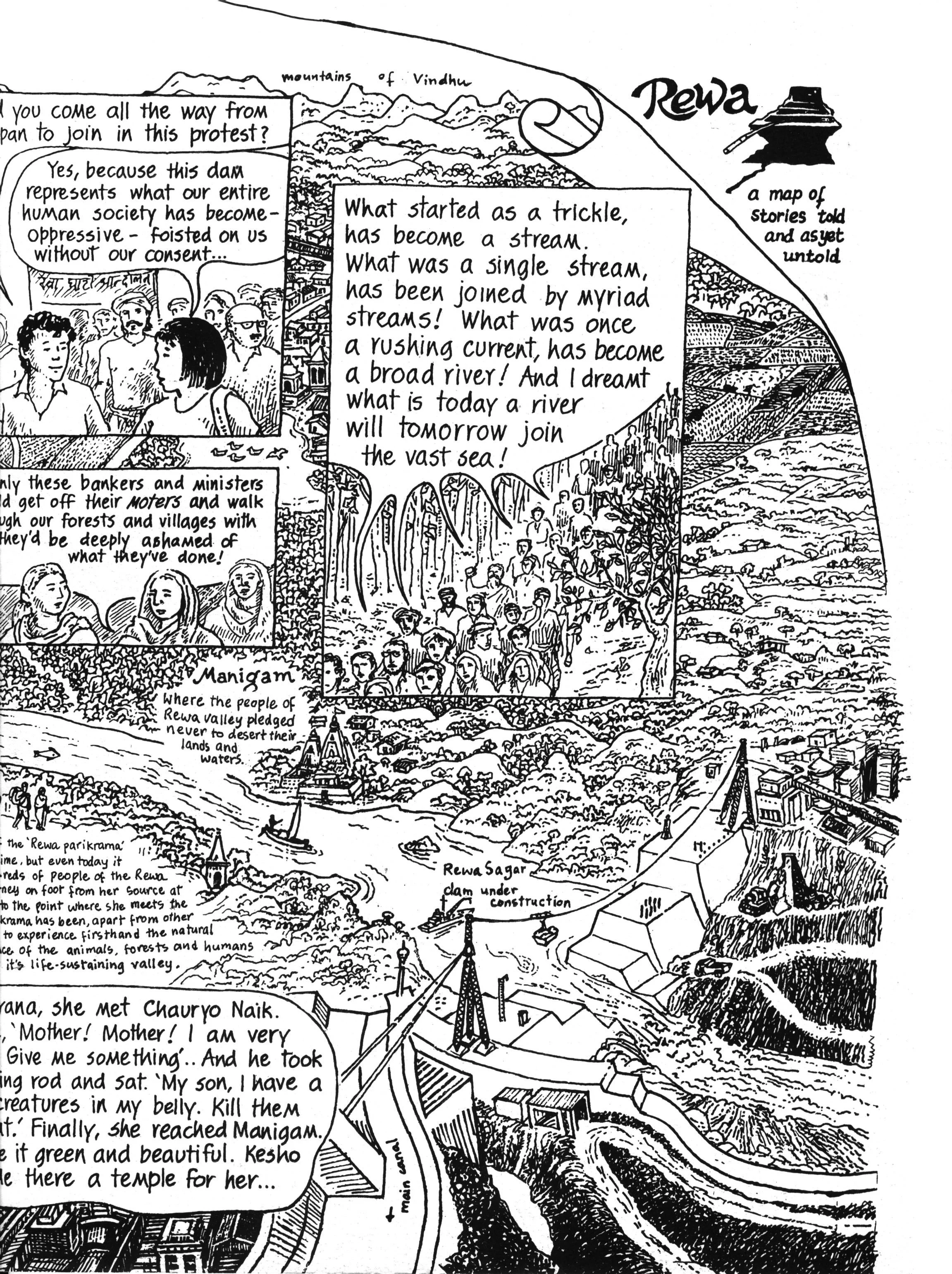

Slipped into the pages of the novel is a surprise by Sen: in a three-page-pullout, he creates a map of the landscape touched by the river Narmada (locally known as Rewa) from its source in Ambarkhant to the dam that spurred the protests. Dotting the map are several scenes from the swelling protests, as well as the ringing chants in Hindi. In a corner of the pullout, a note from Sen reads, ‘Rewa, a map of stories told and as yet untold.’

“The shopkeepers didn’t know which section to stock it in.”

The graphic novel, illustrated entirely by hand, took Sen three years to complete. “I was working in my studio at the People Tree store, which by then, had become a hangout spot for activists, artists, and the creative community. There were always people hanging out, chatting over a cup of chai,” he says. Sarnath Banerjee and Vishwajyoti Ghosh, who’d go on to lead the next generation of graphic novelists in India, often came in to watch him work. “I remember Sarnath in particular. He was very interested in the medium and always full of questions,” says Sen.

By the close of the project, Sen managed to secure a grant from the environmental-issues NGO Kalpavriksh to print 800 copies of the novel, essentially “using a government grant to make a book supporting an anti-government protest.” Although a small pool of artists and designers understood and appreciated the medium, when the novel finally did publish in 1994, hardly anybody knew what to make of it. “I tried to sell my share of the copies to different bookstores, but none of them seemed to understand it,” says Sen. “Was it a comic for children? If so, why didn’t it have color? The shopkeepers didn’t know which section to stock it in. I went to virtually every bookshop in Delhi.”

Detail from Sen’s Khalsa Museum mural

It wasn’t until a decade later that the book began to garner a cult following. After Banerjee published his book Corridor and mentioned River of Stories in an interview, readers began arriving to the People Tree to photocopy Sen’s last remaining copy.

Last year, as the graphic novel turned 25, Sen finally decided to publish a new edition, slated to be launched in December 2020. “A lot has happened since I wrote River of Stories: The Narmada Bachao Andolan itself has moved on; water has flown under the bridge, quite literally,” he says. “Whenever I thought of a new edition, I wanted to create an illustrated preface which would contextualize the scenario in the early ’90s, and how things have changed now, both in terms of the Narmada valley, but also in the larger position of the adivasi and indigenous people, but somehow I never got around to it.”

It was Sen’s daughter who finally convinced him to reprint it as is. “She reminded me to see it for what it is: River of Stories might be the first Indian graphic novel, but more importantly, it is almost a historical document that represents a crucial moment in time in the Narmada Andolan,” he says.

Since his debut, Sen’s work has become increasingly complex and layered. With a career that spans over 30 years, and an oeuvre that began with a graphic novel then moved through non-fiction comics, installations, and murals, he has become one of the most recognizable and celebrated names in the Indian design community. His proclivity to dig into pockets of culture and tell the most unnoticed stories is felt in his panoramic mural at Virasat-e-Khalsa museum and his installation Mapping Mapusa Market, in which he depicts the market in North Goa “that accommodates everything from locally-grown pumpkins, handcrafted products, imported wines to Chinese electronics.”

Mapping Mapusa Market

He’s currently working on a graphic novel called Gokulnagar, in which he delves into the lives of a community of sex workers in a red-light area called Gokulnagar in Maharashtra, who fought to establish their right to practice their profession with dignity, and have now become a force to be reckoned with. It’s impossible to separate Sen’s work from the intrinsic strands of socio-political commentary that run through it. “It is just how I see the world, and these are the stories that I want to tell,” he says.

This article was originally published on Eye on Design.