How Designers in India Turned Digital Tools into Virtual Grounds of Activism

During the Anti-NRC and CAA protests in February, digital platforms helped move messaging from the internet to the streets

In the early hours of February 24, 2020, otherwise quiet neighborhoods in North East Delhi erupted into violent riots as Hindu men rampaged through the streets, attacking Muslim residents, gutting homes, and razing shops and businesses to the ground. It began when a mob of Hindu extremists gathered in the town of Jaffrabad in Delhi to disperse a peaceful anti-CAA sit-in protest by women. The violence that ensued left 53 dead, two-thirds of whom were later identified to be Muslims.

The violence came in the wake of deepening religious divides spurred by the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). The CAA was introduced in December 2019 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s governing far right Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). When combined with the NRC, which was originally mandated in 2003 but is anticipated to be implemented widely by 2020, the CAA makes it easier for non-Muslim migrants from neighboring Muslim-dominated countries to gain Indian citizenship. The law effectively others Muslim communities and undermines the foundations of a secular India, and it’s triggered India’s longest period of unrest in 40 years.

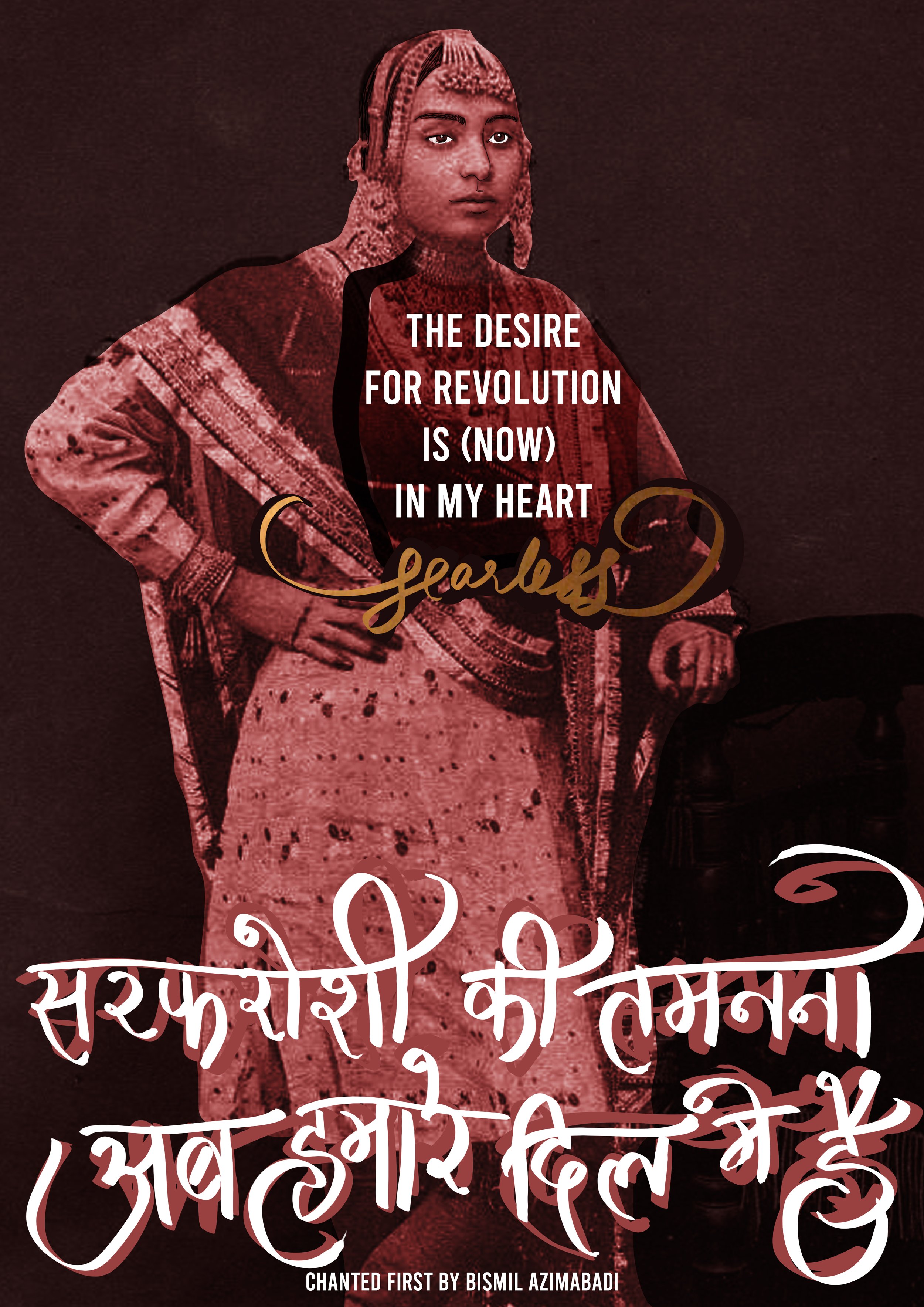

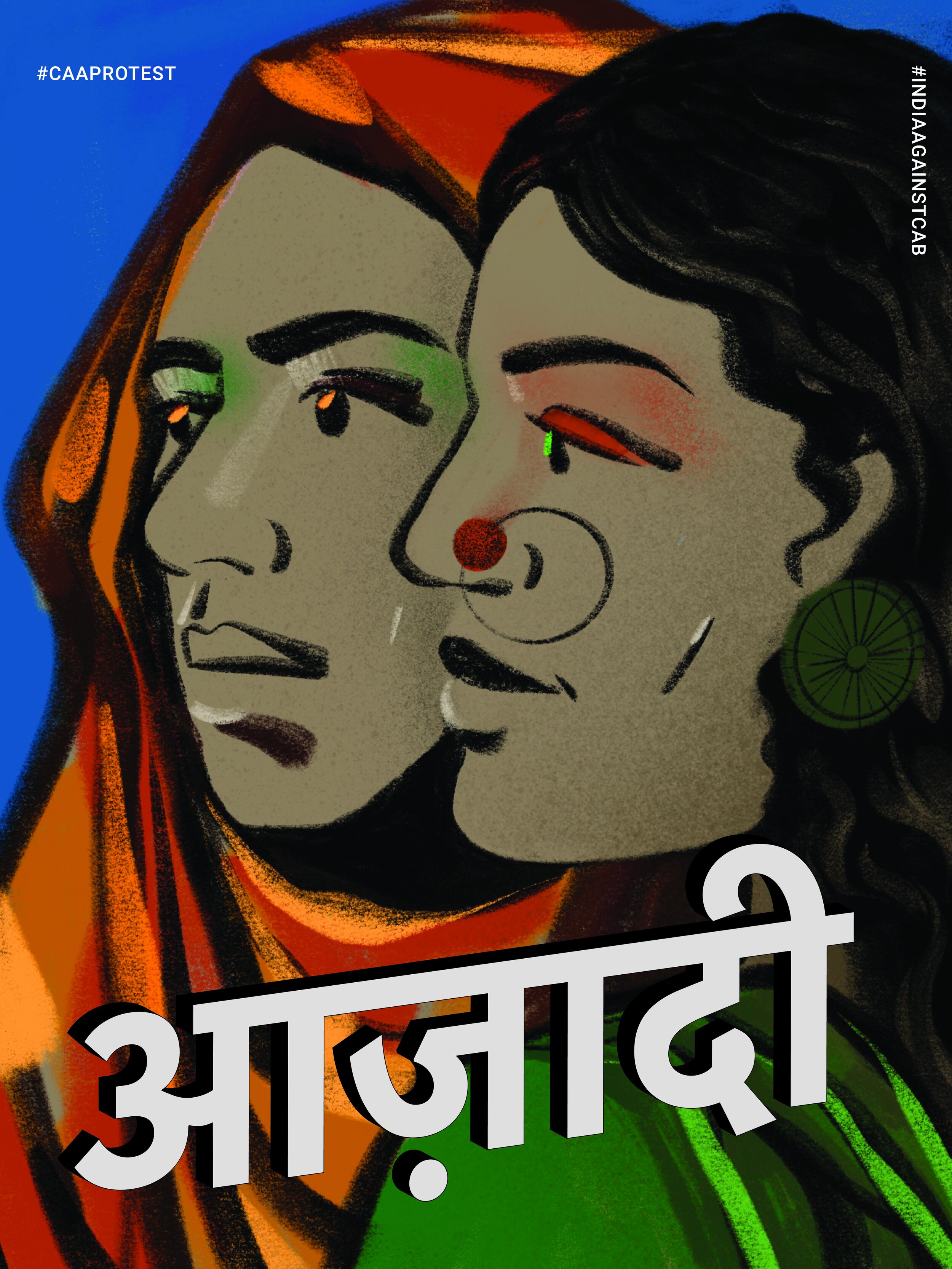

Protesters of all religions took to the streets across the country, armed with handmade posters and hand-lettered flyers. Simultaneously, designers, typographers, and artists began sharing protest art and assets via Instagram and Google Drive, turning these digital tools into a virtual ground of activism. From typographic designs against fascism, to hand-painted posters promoting the ‘oneness’ of Hindus and Muslims, I watched as these artworks moved from the digital sphere to the streets. Some even found their way to international protests peppered across Paris, Berlin, London, and Washington.

Throughout the history of political protests—from the practice of pamphleteering to the radical publishing of the 20th century to today’s digital dissemination of protest art—artists and designers have innovated ways to efficiently proliferate their messages. In the anti-NRC/CAA protests in India, designers contributed to this legacy with the use of open-source tools like Google Drive, which together with social media, quickly spread the messages that protesters would take with them to the street.

“Throughout the history of political protests, artists and designers have innovated ways to efficiently proliferate their messages.”

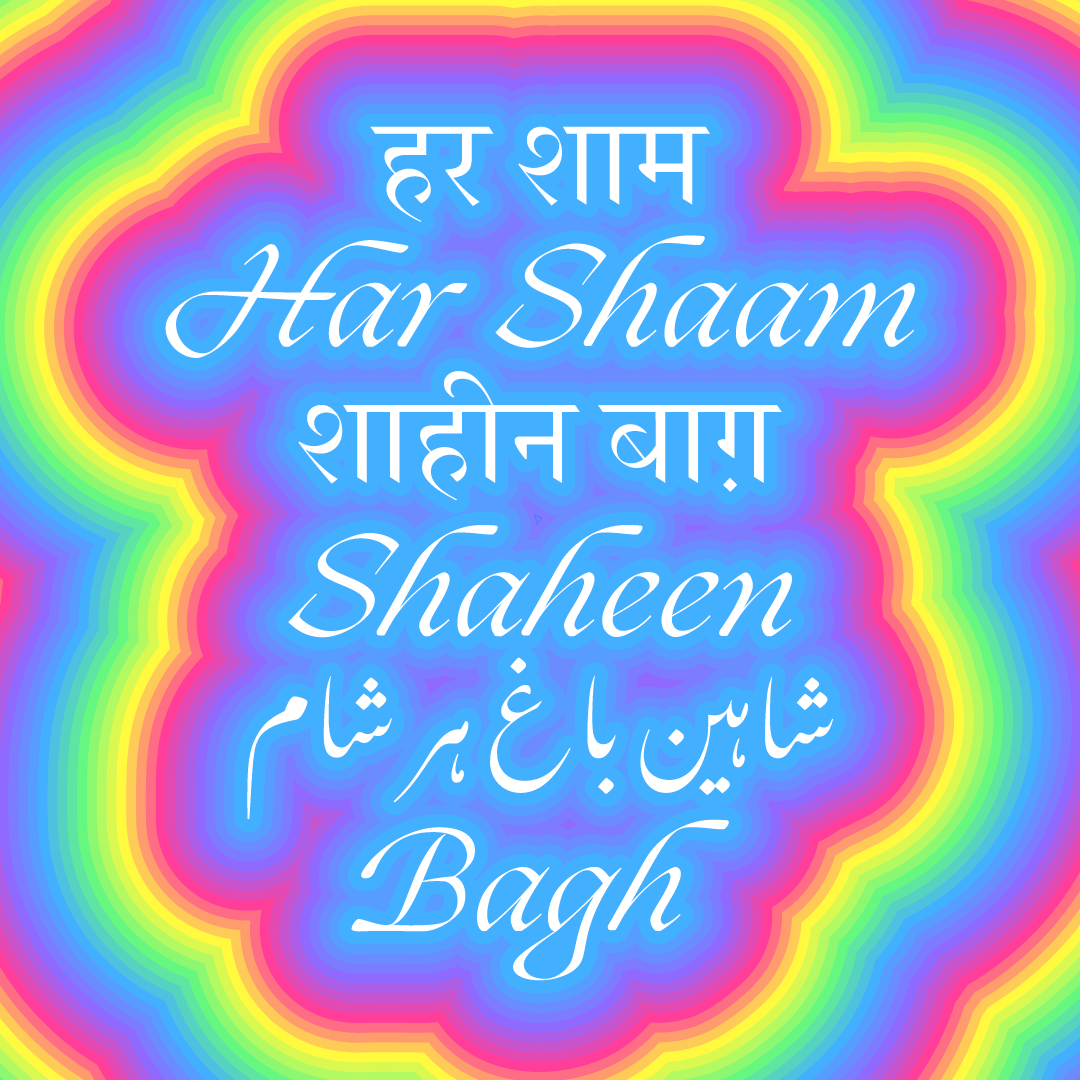

Shiva Nallaperumal, designer and co-founder of the studio November, compiled a bank of assets on Google Drive to arm student protestors who were battling unimaginable state-sponsored police brutality. The folder included posters he designed that read Hum Dekhenge (We Will See) and Har Shaam Shaheen Bagh (Every Evening Shaheen Bagh), as a celebration of the spirit at one of the longest sit-in peaceful protests led by women at Shaheen Bagh in Delhi. He also shared his typeface Unite, a stencil type inspired by the ubiquitous municipal lettering style seen all over India, as well as other digital assets for open use.

File-sharing systems like Google Drive “greatly help in democratizing the process as they enable the sharing of tools as much as information,” says Nallaperumal. The assets he shared, such as fonts, logos, and print files, allowed people to build on his work in their own way. “This, I don’t think was possible before this era. I think this is a key aspect of the current movement: the easy sharing of tools.”

“I think this is a key aspect of the current movement: the easy sharing of tools.”

Creatives Against CAA bypassed Google Drive and created its own repository for downloadable images and communication materials that condemn the citizenship laws. Created by Kadak, a collective of South Asian artists, women, and queer folk who work with graphic storytelling, the website features animated giphy stickers, flyers, and posters made by designers across India. “We wanted to use our skills to enable people to participate in the protests, no matter where they were in the world,” says Mira Malhotra, one of Kadak’s eight members. “We wanted to make protests a thing they can and should engage in.”

Even before the revolution moved to Google Drive and websites, designers had been sharing images of protest on Instagram. The idea of Creatives Against CAA, for example, was sparked when Kadak came across the work of a score of artists and designers on the platform. Nallaperumal also first began sharing his posters on the platform, and when he began compiling the assets on Google Drive, he shared the link to the folder on his bio, as did many other designers. Not long ago, Twitter was the global platform for revolutions, but Twitter’s bite-sized portions of thoughts and ideas can make for a lack of context, says Malhotra. “However, on Instagram every post is led by a visual, which makes it extremely different from Twitter,” Malhotra says. “Thoughts can be presented with nuance, ideas can be explained, often without the need for written text. Comics and explainers can approach a difficult or inflammatory topic with humor, familiarity, and nuance.”

“Comics and explainers can approach a difficult or inflammatory topic with humor, familiarity, and nuance.”

With its immediate and global reach, Instagram has a compelling ability to connect people and harbor a sense of community, especially in tumultuous times. A protest piece shared on Instagram by designer Anirban Ghosh, found its way to the walls of Jamia Millia Islamia, a university in New Delhi which has become a nucleus for student-led protests. The students at Jamia found his work on Instagram and Google Drive, and invited him to the capital to turn one of his artworks into a mural on the walls of the university. Ghosh’s piece turns Varun Grover’s poem Hum Kagaz Nahi Dikhayenge (We Won’t Show Our Papers)—a response to the NRC demanding decade-long Indian residents to furnish documents as proof that they belong to India—into a series of illustrations. “The opportunity to be in Delhi along with the other students would never have come along if they hadn’t found my work, and connected to it, on Instagram,” says Ghosh.

To battle the worst prejudices of the BJP government, the revolution on Instagram and Google Drive, led by activist-designers, gives an identity to the movement and arms the everyday Indian with the agency to participate in the resistance and voice their opinion. It’s importance is felt even more sharply today, as COVID-19 has taken protestors off the streets, while the government has prioritized painting over murals by protestors, even during a global pandemic. But the task of helping communities magnify their voices and ideas is not one to be taken lightly. “I would advise all young designers to engage with history and political theory, and be conscious of the magnitude of the movement,” says Nallaperumal. “Form your own opinion and know the power of the image.”

This article was originally published on Eye on Design.